Fannie Lafontaine

Fannie Lafontaine est professeure de droit à la Faculté de droit de l'Université Laval et directrice de la Clinique de droit international pénal et humanitaire.

Pour plus d'information, cliquez ici.

Analyse - Analysis

By Fannie Lafontaine

Professor, Law Faculty, Laval University (Quebec City)

Canada Research Chair on International Criminal Justice and Human Rights

Founder and Co-Director of the International Criminal and Humanitarian Law Clinic

Author of Prosecuting Genocide, Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes in Canadian Courts (Carswell: 2012).

Regular member of the Institut québécois des hautes études internationales

Introduction

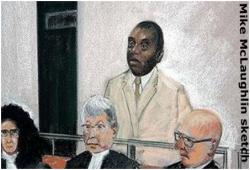

The confirmation of conviction and sentence of Désiré Munyaneza by the Quebec Court of Appeal on 7 May 2014 (the official French version is here), for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Rwanda in 1994, is significant both from a Canadian perspective and more generally with respect to the principle of universal jurisdiction for the gravest international crimes. This (rather long, apologies) post summarises and analyses à chaud some of the most important legal issues tackled by the 388-paragraphs judgement. It also considers broader policy questions related to Canada’s relationship with the alleged war criminals present here (for media reports of the decision, see here and here, among others).

At the time of writing, Munyaneza has not announced his intention to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. Considering the unanimous decision of the Court of Appeal, he must be granted leave to appeal (automatic right of appeal in criminal cases is only where an acquittal was set aside or in cases where one judge dissents on a question of law). Leaves to appeal are discretionary and can be granted if the case involves a question of public importance. This includes, for instance, a novel point of law or interpretation of an important federal statute. The judgement of the Quebec Court of Appeal is solid and is the only case emanating from a court of appeal interpreting the Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Act (2000) (the Act) as of yet. The Supreme Court might be inclined to wait until and if conflicting judgements come out of different provinces. It might also wait for a case that deals with a broader range of issues of law emanating from the Act, such as principles of liability or defences, which were not at issue in Munyaneza. But this is pure speculation.

The Background and the Appeal

Munyaneza was the first case under the Act, and as such, a test case. To recall, on 22 May 2009, Munyaneza was convicted in first instance by Denis J. of the Quebec Superior Court of seven counts of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes for acts of murder, sexual violence and pillage committed in Rwanda in 1994. On 29 October 2009, Mr Munyaneza was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years, the harshest sentence available in Canadian law, automatic when planned and deliberate murder is involved. As I have argued elsewhere (see here), the lower court’s judgement was hard to reverse on the law. The legal analysis was contained in some 25 pages of a long judgment that mainly focused on the evidence substantiating the indictment. The legal discussion was written in broad strokes and, while it was not infallible, it was in general conformity with international law and a good first interpretation of the Act. The Court of Appeal did not directly reverse any of the legal findings of the judge below, but the judgement is - as is often the case on appeal- much more meticulous in its legal reasoning and represents a solid precedent on the law applicable to international crimes in Canada.

The appellant (defended by competent counsel with experience in both Canadian criminal law and at the ICTR) raised several grounds on appeal, which the Court grouped into five categories (para. 14), slightly reformulated as follows:

- The acts of murder, sexual violence and pillage, of which he was indicted as “war crimes” committed in a non-international armed conflict, do not constitute war crimes according to international law in force in 1994 or, in the alternative, according to Canadian law in 1994;

- The invalidity of the indictment on grounds of vagueness;

- The commission of irregularities by the judge, rendering the trial unfair;

- The judge's misinterpretation of the constitutive elements of the alleged offences; and

- The clear lack of credibility of the Crown's witnesses, invalidating the verdict.

I will address in more detail grounds 1 and 4, which concern substantive law, and ground 2, which became a particularly important issue.

The Evidence

Briefly, on ground 3, the Court rejected the Appellant’s claims that the fairness of the trial had been affected by a visit of the judge, without his knowing, to Butare. Judges on rogatory commission are however put on notice that this is not such a good idea: “it would undoubtedly have been preferable if the judge had refrained from visiting this city without speaking to counsel about it beforehand. Nevertheless, the record shows that the judge was there purely as a tourist and that his visit did not have the objective of moving the trial forward…” (para. 92-101). The Court also rejected the claim that the judge inappropriately used a book by Alison Des Forges, which had not been adduced into evidence (para 102-110), and concluded that the inclusion of a wrong exhibit in a schedule to the judgement had no impact on the fairness of the trial (para. 111-119).

The Court of Appeal devoted the last 180 paragraphs of the judgment to ground 5 related to the assessment of the evidence by the judge (para. 208-388). A Court of Appeal must “give due weight to the advantages of the trier of fact, who took part in the trial and saw and heard the testimony” and “should therefore refrain from interfering with the trial judge's findings of fact unless the appellant can demonstrate a palpable and overriding error in the judge's assessment of the evidence or a failure on the part of the judge to consider a significant part of the evidence”. However, “the reviewing court must nevertheless weigh the evidence and consider whether, through the lens of its own experience, judicial fact-finding precludes the conclusion reached by the trier of fact – or in other words, whether the verdict is reasonable in light of the evidence”. Also, “if the judge has ignored legal rules in applying his or her own analysis to the evidence, however, and this error might have influenced the verdict, the appellate court must intervene”. (para. 209-211, referring to R. v. W.H., 2013 SCC 22, [2013] 2 S.C.R. 180).

The outcome of the appeal in this case, which was based on complex facts and unusual evidence, lied in the evaluation of the reasonableness of the finding of guilt. The Court of Appeal was unequivocal and rejected all of the Appellant’s arguments. In bulk:

- On the caution to himself concerning factors likely to seriously impair the credibility of a witness (the “Vetrovec warning”), the judge “took note of the weaknesses in the testimony and explained his decision to accept them nevertheless, either in whole or in part (para. 218);

- On the identification evidence, the judge’s treatment of the photo lineup identification evidence “reveals that the threshold of objective reliability was reached” (para. 221 ss);

- On contamination and collusion (an argument that was fatal to the Crown in the Mungwarere case, as mentioned below in footnote 1), many of the Appellant’s allegations were found to be “speculative” or “insufficient” (para. 229, 230), and, in cases where there could have been collusion, “on which the Court takes no position, its effect was merely collateral” (para. 234).

- On the individualized assessment of the sixty-six witnesses the judge heard, in relation to the involvement of the accused at the Ngoma church, at the prefectural office in Butare, at the roadblocks erected in this city, and in various other locations, as leader of a group of the Interahamwe, the Court of Appeal upholds the judge’s assessment to conclude that “the evidence establishes that the appellant had the intent to attack Tutsis specifically and that he was at the forefront of the armed conflict in the Butare prefecture” (para. 372). The detailed analysis by the Court of Appeal runs on 150 paragraphs and confirms the reasonableness of the verdict of guilt “rendered on each of the counts against the accused in light of the elements of each of the offences”, as a principal perpetrator (para. 368).

The Law

The three other grounds of appeal allowed the Court of Appeal to clarify the law applicable to international crimes prosecutions in Canada. It was a first case and the Court had to break new ground, and so it did. Carefully looking to international jurisprudence and inspired by the doctrine (kudos here to my colleague Robert J. Currie of Dalhousie for greatly contributing to a sensible development of the law), the Court of Appeal paved the way for a sensitive application of the Act and for the development of Canadian law in harmony with international law.

Ground 2 -Validity of the indictment

This is an argument that was dear to the Appellant, and which took an important place in the appeal. Munyaneza argued that the counts did not meet the degree of precision required by the international criminal tribunals, thus rendering his trial unfair. As an example, Count 1 of the Indictment read as such:

[TRANSLATION]

First count:

Between April 1, 1994 and July 31, 1994, in the Prefecture of Butare, in Rwanda, committed the intentional killing of members of an identifiable group of people, to wit: the Tutsi, with intent to destroy the Tutsi, in whole or in part, committing an act of genocide, as defined in subsections 6(3) and 6(4) of the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act, S.C. 2000, c. 24, thereby committing the indictable offence of genocide, as provided for in subparagraph 6(1)(a) of the said Act.

In Munyaneza’s view, “the location of the alleged offences, the identity of the victims, and the nature of the incidents at issue should have been precisely identified in each of the counts” (para. 61) and he referred to the rules and practice at the ICTR in support of his argument. He argued “that this degree of detail is also required under the Charter [of Rights and Freedoms], particularly paragraph 11(a) (the right to be informed without unreasonable delay of the specific offence), paragraph 11(h) (the right not to be tried again for the same offence), and section 7 (the right to a fair trial and to make full answer and defence), especially since the charges are complex, involve several events, and contemplate very harsh sentences” (par. 63).

The Court of Appeal did not agree: Canadian procedure applies to prosecutions under the Act as per Sections 9 and 10 of the Act (para. 68) and hence “[t]he validity of the indictment and its impact on the fairness of the trial must be analyzed under Canadian rules” (para. 72). The Court analysed the applicable rules, into which I won’t delve here, and concluded to the sufficiency of the counts. Noting the “contextual elements” of the crimes at play, namely the specific intent of the crime of genocide, the attack element of the crimes against humanity and the armed conflict for war crimes, the Court concluded that a count could “encompass a series of similar acts committed during a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population, either in the context of the destruction of an identifiable group of persons or during an armed conflict, and still not violate the single transaction rule. The context reveals a course of conduct that includes the commission of underlying acts, which may then be grouped together, according to their nature, in a single count and constitute a single transaction” (para. 79). The Court also took into account the information disclosed to the accused by the Crown ahead of trial in its assessment of “whether the appellant had sufficient knowledge of the theory the Crown intended to present to be able to prepare an adequate defence against the charges” (para. 86).

It remains to be seen how future indictments should look like. Although the Court of Appeal did not criticise the Crown for proceeding the way it did, it did say that it “could have drafted one count for every incident”. Furthermore, in the only other case under the Act, the accused Jacques Mungwarere also contested the indictment in the procedures against him.[1] The Court did not either accept his arguments on this issue, but it certainly signals a malaise in the interaction between Canadian procedural law and international crimes from the Defence’s point of view. The Court of Appeal’s decision is a welcome clarification, but certain issues remain outstanding, particularly in the event of a trial before judge and jury, which was not the case for Munyaneza and Mungwarere.[2]

The application of Canadian procedural law to international crimes has not been studied in great detail as of yet and it is a fertile ground for further research, as this author is beginning to do.

Ground 1: War crimes in non-international armed conflicts in 1994 and “retroactive” application of the law

The Appellant brought two main arguments: first, he could not be indicted for war crimes because such crimes did not exist in 1994 in international law where committed during a non-international armed conflict. He argued that such acts only became crimes according to international law in 1998 with the adoption of the Rome Statute. Moreover, according to him, pillage of a home and of businesses would still not constitute a crime in international law, which would require pillage of a town or place. Second and alternatively, he argued that if such crimes existed in international law in 1994, they could not be prosecuted in Canada because at that time, the Criminal Code only criminalised war crimes committed in international armed conflict. Applying the Act adopted in 2000 would be retroactive in effect, which he argued is prohibited under paragraph 11(g) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

On the first argument, it was a fair deal for the Appellant to try it out. It was the first prosecution in Canada for war crimes committed in a non-international armed conflict. The Act relies extensively on customary international law for the definitions of the crimes. It uses the Rome Statute as an interpretative device of customary international law, in an apparent effort to facilitate the task of the judge in this difficult endeavour. The Act indicates, at. s. 6(4), that:

For greater certainty, crimes described in articles 6 and 7 and paragraph 2 of article 8 of the Rome Statute are, as of July 17, 1998, crimes according to customary international law, and may be crimes according to customary international law before that date. This does not limit or prejudice in any way the application of existing or developing rules of international law.

However, for crimes committed before 17 July 1998, like obviously during the Rwandan genocide, the Act does not mandate an interpretation of customary international law in accordance with the Rome Statute. The judge has to make his or her own interpretation (see para. 27 of the Court of Appeal judgment, and generally my book on the issue[3]). Considering the absence of treaty provisions for war crimes in non-international armed conflict (in 1994), the liability of the Appellant depended on the existence of the crime in customary international law.

It was perhaps reasonable for the Appellant to make his case, but it was an uphill battle from the start. The Court of Appeal heeded on the advice of the Supreme Court of Canada in Mugesera and turned to the jurisprudence of international criminal tribunals to resolve this issue (para. 30), as it was also invited to do by the interveners the Canadian Center for International Justice and Canadian Lawyers for International Human Rights. It relied on Tadić and Akayesu and concluded without hesitation that “there can be no doubt that, in 1994, war crimes comprised serious acts such as murder and rape, an act of sexual violence constituting serious harm to the integrity and dignity of victims that were committed during a non-international armed conflict in Rwanda” (para. 33). As for pillage, it clarified that it, too, was a crime under customary international law at that time (para. 34) and rejected the Appellant’s argument that only pillage of a town or place is encompassed by the criminalisation (see the detailed analysis at para. 191-197).

The Court concluded “that, before 1994, the underlying offences alleged in the fifth, sixth and seventh counts [murder, sexual violence and pillage] committed during a non-international armed conflict were war crimes according to international law” (para. 45). From an international law perspective, the Appellant’s argument was almost a non-starter. But it flowed naturally from the legislative choice made in the Act to leave the determination of customary international law to the judge for crimes committed before 17 July 1998. The Court of Appeal’s unambiguous pronouncement is important for Canadian law and a firm precedent on war crimes committed in non-international armed conflicts.

As for the Appellant’s argument regarding the alleged retroactive application of the 2000 Act to acts committed in 1994, this, too, was like a sword strike into water. As the Court aptly recalls: “[t]he Act does not attempt to create an offence ex post facto. Rather, it seeks merely to allow the prosecution in Canada of persons who, before the Act entered into force, committed acts that, at the time of their commission, constituted genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes, according to the definitions of those crimes under international law…” (para. 51). “The Act is thus consistent with paragraph 11(g) of the Charter, which recognizes that the criminal nature of an act at the moment it is committed may be assessed under either domestic or international law” (para. 52). The possibility of trying war criminals from the Second World War was explicitly discussed and envisaged during the negotiations of this particular Charter provision. The Court’s conclusion is also consistent with international human rights law, as is well known, and in line with the Finta decision of the Supreme Court of Canada of 1994.

A first case serves to confirm (or not) the solidity of the foundational legislative regime upon which it lies. The Court of Appeal did it again: “the Act validly permits the prosecution of an individual in Canada for a war crime committed before 2000” (para. 55). In addition to the clear provision in the Act concerning crimes against humanity, which were “part of customary international law or [were] criminal according to the general principles of law recognized by the community of nations before [1945]” (s. 6(5)), there is now close to no window for alleging that the Act violates the guarantee against the retroactive application of the law (see section 3.2.1.1 of my book).

Ground 4: Constitutive elements of the crimes

The Appellant principally took issue with the interpretation of the war crime of “pillage”, as noted above, but the Court noted that “in a manner that was at times rather vague, counsel for the appellants faulted the trial judge for his outline of the elements of the other crimes, particularly his definition of what constitutes murder, arguing that he selected a Canadian and not an international definition of this underlying offence” (para. 121). The Court thus took the opportunity to clarify the constitutive elements of all the offences for which the Appellant was charged, an important step in this first appellate judgement interpreting the Act.[4]

This is not the place to engage with all of the conclusions of the Court as regards each offence. They will be dissected in a further analysis. The Court systematically turned to international jurisprudence, as well as to the Supreme Court’s decision in in Mugesera where relevant to do so. Its analysis is consistent with the law as it stood in 1994 and I do not think there are any real problematic findings. One general warning, though: as mentioned above, the Act mandates an interpretation of the crimes committed after 17 July 1998 in accordance with the Rome Statute. In a few instances, this may have a non-negligible impact on the constitutive elements of the crimes as they should be interpreted in any future case related to crimes committed after that date, departing in some instances from the findings of the Court of Appeal in Munyaneza and indeed the Supreme Court in Mugesera.[5]

Some findings of the Court should also be treated with caution, as they may have been influenced by the law that was applicable at the time and place the crimes were committed (1994), but that would not be justified nowadays. One example relates to crimes against humanity: the Court provides a definition of “civilian population” that is unduly restrictive, appearing to insist on characteristics of the group (ethnic and political) (para. 146-147), whereas international law does not impose such requirements so as to further distinguish the crime against humanity from the crime of genocide (see wonderful thesis from William St-Michel, section 2.2 on this issue). With respect to war crimes, there are a number of anomalies, which may be of more interest to international law geeks like me than some future Canadian judge applying the Munyaneza precedent. Nevertheless, they are susceptible of creating confusion. For instance, at para. 288, the Court summarises the constitutive elements of war crimes thus:

To prove that a war crime has been committed, in addition to the material and mental elements of the underlying offence, the following contextual elements must be established:

- an armed conflict, whether international or not;

- offences committed against persons who did not take part or who had ceased to take part in the armed conflict, or in other words, protected persons;

- a nexus between the offences committed and the armed conflict; and

- the accused’s knowledge of this nexus. (my emphasis)

The underlined part is problematic: for one, war crimes can be committed against active combatants (numerous examples at Art. 8(2)(b) of the Rome Statute) and for two, the concept of “protected persons” is reserved for international armed conflicts. The Court appears to confuse the “grave breaches” provisions it discussed in the preceding paragraphs (limited to international armed conflicts and concerned with “protected persons”) with the law more generally applicable to war crimes, that goes beyond the “grave breaches” regime, in non-international armed conflicts obviously, but also in international armed conflicts.

For our purposes here, I will highlight one important finding by the Court that is more specific to the Canadian legislative framework and that will influence future jurisprudence: the underlying offences of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes must be interpreted in light of international law (para. 123-129). This may seem trivial, but the issue of which body of law should apply to offences that have a domestic equivalent (murder, torture, sexual violence) was already source of confusion in the emerging jurisprudence and had never been explicitly ruled upon. There was no clear authority on this question and the Court of Appeal thankfully filled the void. The Court used principles of legislative interpretation to come to that conclusion, highlighting also the “dichotomy” that the opposite conclusion would create.[6]

The consequence of this important ruling is that “known” domestic offences, particularly murder, sexual assault and torture, have different meanings where they are treated as underlying offences of international crimes. In Munyaneza, the Court clarified the law applicable to murder and made an important finding with respect to causation:

Murder under international law thus differs from murder under Canadian law in one respect, since the latter requires a lower standard to establish a causal connection between the accused's conduct and the death. As Professor Lafontaine points out at page 127:

In Canadian law, all that is required is that the conduct be a "contributing cause of death, outside the de minimis range” or, as rephrased in a later judgment by the majority of the Supreme Court, a “significant contributing cause”. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the terminology of “substantial cause” to describe the requisite degree of causation for all homicide offenses and indicated that this involved a “higher degree of legal causation”.

To remain consistent with the applicable law – i.e., international law – the higher standard of causation must be met. It follows that, with respect to causation, the prosecution must establish beyond any doubt that the act committed was a “substantial cause of death” ("cause substantielle de la mort”) and not merely a "significant contributing cause of death" ("cause ayant contribué de façon appréciable à la mort"). (para. 136-137) (my emphasis)

As regards sexual violence, there are a number of interesting findings, but let me mention two:

- The crime of rape is back. In Canadian law, the crime of rape was replaced in 1983 by the more gender-neutral and broader term of sexual assault. The Act, by referring to international law, thus reintroduces the crime of rape in Canadian law where international crimes are involved, a conclusion confirmed by the Court of Appeal.

- The Court of Appeal does not expand greatly on the material and mental elements of the crime of rape and of the broader crime of “sexual violence”. This is a little disappointing, as the Court lost an opportunity to adopt a progressive definition and contribute to both clarification of the crime in Canadian law and to the development of international criminal law. The Court nevertheless usefully confirms – in light of a long-standing debate in international law- that “while the use of force or the threat of force may be used to establish lack of consent, it is not an element of rape, whereas lack of consent is” (para. 140, 154ss). However, its adoption of the more restrictive definition of the material element of rape, as in Furundžija[7], might need more nuances in the future to better reflect the evolution of international criminal law in this regard and be more gender-neutral.

The crimes of rape and sexual violence will certainly have to be further developed in future cases.[8] In particular for crimes committed after 17 July 1998 - where the Rome Statute must govern the definition of the crimes as per s. 6 (4) of the Act- the definition adopted by the Court of Appeal might have to be slightly revisited (see brief discussion here and a more fletched out one at section 3.3.3 of my book).

Conclusion

???

???

The Quebec Court of Appeal, with a superstar bench[9], delivered a convincing judgement on the law and facts, which says at least one thing about the international system: national courts can be up to the task in the global fight against impunity. The decision tells us a further thing, more particular to this country: Canada has a strong piece of legislation that fulfils the primary objective of its adoption, that is to retain and enhance Canada’s capacity to prosecute and punish persons accused of the “core” international crimes.

Be that as it may, the Act’s ultimate success perhaps depends not so much on the strength of its provisions or judicial interpretations, but on the political will to use it to its full extent against international criminals found on Canada’s territory. Prosecutions in Canada are allowed only with the consent of the Attorney-General of Canada, a worldwide tendency that serves to limit the adverse diplomatic consequences of universal jurisdiction, but that presents the risk of sacrificing justice and the rule of law on the altar of political and economic concerns.[10]

Munyaneza could have signalled a possible return to a more aggressive stance regarding alleged war criminals found on Canadian territory. However, what we see today is hardly any different than 20 years ago after the debacle of the Finta prosecution: immigration measures are preferred, prosecution is hardly an option. The last annual report of Canada’s war crimes program is more explicit than ever: “The War Crimes Program emphasizes immigration remedies, namely denying visas and denying entry to Canada to persons who are inadmissible to Canada under the IRPA. Immigration remedies have been found to be effective and cost-efficient. The most expensive and resource-intensive remedies are the criminal investigation and prosecution of war criminals – these methods are therefore pursued infrequently”. The political message coming from the Government is even more explicit: “It's not up to Canada to prosecute people suspected of crimes against humanity… Canada is not the UN. It's not our responsibility to make sure each one of these faces justice in their own countries”.

As things currently stand, the vast majority of individuals alleged to have committed international crimes are indeed excluded from Canada and not sent back to face trial abroad. According to the same last annual report, as of March 2011, five hundred and twenty-seven (537) persons were removed and two (2) persons prosecuted since the inception of the program in 1998. These numbers are telling. The over-reliance on immigration remedies may serve the limited purpose of not allowing Canada to become a safe haven for war criminals, but does very little to serve the broader objective of ensuring accountability for the core crimes.

What should Canada do with suspected war criminals present here? Between the self-proclaimed pragmatists (we can’t prosecute more) and the “idealists” (we must prosecute more), it’s perhaps time to think creatively of what could be termed ‘alternative universal justice’, or innovative forms of justice that would acknowledge the inherent practical impossibility of trying in a criminal court all potential suspects of international crimes present on a third state’s territory while giving due recognition to the fundamental principles of justice, accountability and reparation (see chapter 6 in this new book edited by my colleague Jo-Anne Wemmers).

But all things pondered and considered, prosecutions on the basis of universal jurisdiction must remain an option: they are essential for the “sustainable development” of international criminal justice (see here). Justice for international crimes is indeed a long and winding road. But the Quebec Court of Appeal just erected a helpful road sign that reads: “This way”.

[1] Mungwarere was eventually acquitted in a case that ended quite dramatically for the Crown. The judge concluded to the fabrication of evidence against the accused by witnesses and his assessment of the remaining credible evidence did not convince him beyond a reasonable doubt of the accused’s guilt (although the judge unnecessarily said the evidence led to the “probability of guilt”: judgement here). The judgement is now final (the Crown did not appeal) and Mr Mungwarere is subject to deportation procedures (this brings a whole new set of complex questions which go beyond this post but are at the core of the author’s and others’ research).

[2] In Munyaneza, the Court of Appeal put the unresolved issue thus : “For example, can a jury, unanimous as to the commission of genocide, convict an appellant on the first count, if six of the jurors based their finding of guilt on the murders committed near the Ngoma church and the other six based it on the murders committed after the kidnappings at the roadblocks? However interesting this question may be, the Court need not decide it, since this trial took place before a judge alone” (para. 75). In Mungwarere, note also that the judge warned against the use of a jury in a trial for international crimes (para. 23).

[3] Unfortunately expensive (promo code 50% off : 67533) and not available in a digital format. Better: available at your library for free. If not, ask for it! J

[4] Note again that the modes of liability were not at issue, Mr Munyaneza being accused as a principal perpetrator. This issue was rather confusedly addressed in Mungwarere and will need clarification in the future. The application in criminal prosecutions of the principles developed by the Supreme Court of Canada in Ezokola, which concerned complicity in an international crime for refugee exclusion matters, remains to be seen (see comment here).

[5] An example is the applicable mens rea for crimes against humanity, which under the Rome Statute may exclude recklessness: see section 4.2.2 of my book).

[6] For instance, the same underlying offence of “murder” could be interpreted in light of two different bodies of law according to the formulation of the crime: Canadian law for crimes against humanity, because murder is explicitly listed in the definition and hence would call for an interpretation in accordance with the Criminal Code, whereas the same underlying offence would have to be interpreted in light of international law where constitutive of genocide or war crime because the Act there only refers to murder implicitly through reference to international law. See also my book, section 3.3)

[7] “penetration, however slight, of the vagina and anus by the penis or any other object or of the mouth by the penis” (para. 142).

[8] Note that the Crown dropped the charged for sexual violence against Mungwarere.

[9] The Honourable Pierre J. Dalphond, J.A., Allan R. Hilton, J.A. and François Doyon, J.A.

[10] The changes to the universal jurisdiction law in Spain show this risk with particular acuity (see e.g. here). See also on the French debate an excellent paper by Elise LeGall. Élise Le Gall, AJ pénal Dalloz April 2014, « De la cour d’assises de Paris à l’Assemblée Nationale : retour sur la compétence universelle comme instrument de répression des crimes internationaux ».